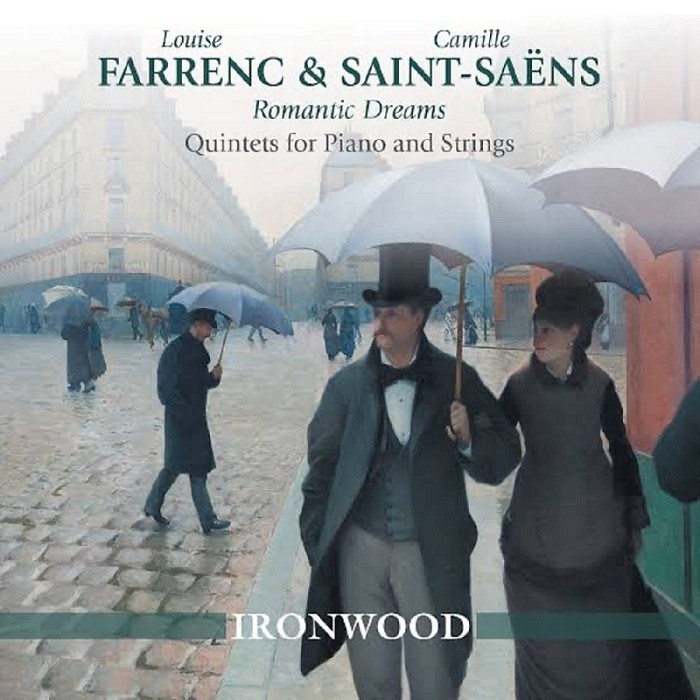

Album Review: Romantic Dreams – Quintets for Piano and Strings/ Ironwood/ ABC Classic

Ironwood’s newest album release, Romantic Dreams – Quintets for Piano and Strings is music made in our time, yet brushed with the patina of age.

Featuring two quintets from the French Romantic era, this recording for ABC Classic, is meticulously researched and performed with artistry and integrity. Even better, the researchers themselves are elite scholar-performers and interpret for us first hand, their understanding of the soundscape, serving as a direct interface between the performance practices of 19th century France and our appreciation of it today.

Comprising violinists Rachael Beesley and Robin Wilson (Saint-Saëns only), violist Simon Oswell, cellist Daniel Yeadon, double bassist Rob Nairn (Farrenc only) and pianist Neal Peres Da Costa, this historically informed performance of Louise Farrenc’s Quintet for piano and strings, No. 1 in A minor, opus 30 (1839) and Saint-Saëns’ Quintet for piano and strings in A minor opus 14 (1855), is presented on period instruments, made in Italy, France and London dating from 1740 to 1915, with the all- important grand piano, an Érard from 1869 Paris.

Why single out the piano? In both these quintets, the piano is gloriously and unapologeticaly the first among equals, reflecting the pianism of both composers.

Farrenc studied with Reicha, Hummel and Moscheles and remarkably for the times, was appointed professor of piano at the Paris Conservatoire, a post she held for three decades from 1842. Her aesthetic in her first quintet is distinctly Classical and traditional in its approach to form and harmony. Her writing makes abundant technical demands of the pianist with sparkling arpeggios, thirds and sixths, amply exploiting the range of the keyboard and its many colours.

In her first quintet, Farrenc replaces the second violin with the double bass, as Schubert did in his ‘Trout’ Quintet. Ironwood opens the first movement (Allegro) in a sombre though lyrical mood, rising in passion, with ornamentation that blooms into more radiant moments. In the second movement (Adagio non troppo), Ironwood creates a gentle dialogue between the piano and the others of the ensemble, with especially tender solo passages from the cello, answered by the violin. A modulation to the minor key leads to a dramatic climax before the theme returns with variants. In the third movement (Scherzo) Ironwood bursts into activity, pressing onward with the rising figures of the Finale subsiding to a paradoxically hushed ending.

As highlighted in the extensive and erudite booklet notes by Peres Da Costa and Yeadon, unnotated arpeggiation and asynchrony were devices used by 19th century pianists, along with teasing the rhythm and tempi, thus articulating and shaping the phrases, “to breathe life into the music.” Using these devices, (especially noticeable in the third movement), along with portamenti and other devices, the distinct sound of Ironwood voicing Farrenc’s lush harmonic progressions, takes us to an extremely engaging rediscovery of Farrenc’s neglected gem.

The second quintet in A minor on this recording, the opus 14 of Saint-Saëns, also places the piano front and centre. Like Farrenc, a pianist as well as being an organist, Saint-Saëns gives the piano a role that is unashamedly soloistic at times but equal in ensemble and sympathetically supportive at others. Ironically, (pardon the near-pun), like Farrenc’s A minor quintet, this quintet too can include the double-bass in the third and fourth movements, to ease the demands on the pianist. Popularly known as a composer of larger orchestral works like his third symphony, the Carnival of the Animals and the opera Samson and Delilah (he wrote 13 operas), the opus 14 is Saint-Saëns’ first, albeit sophisticated venture into chamber music. Composed in his late teens after he left the Paris Conservatoire, it is quite different in outlook to Farrenc’s conservatism, looking forward to a sweeping more rhapsodic style but harking back to counterpoint in the fourth movement.

Peres Da Costa opens the first movement, (Allegro moderato e maestoso) with rumbling arpeggiated piano chords which broaden into sweet and nimble themes alternating with frequent turbulence. The mood of this movement is concerto-like and intensified by the piano’s bass tremolo in its closing bars.

Ironwood gives the lyrical second movement, (Andante sostenuto) a gentle chorale-like feel. The theme, introduced by the piano is answered, developed and varied by the strings. Ironwood returns us to turbulence in the third movement (Presto), rather like a restless danse macabre which despite its disquiet, ends in a radiant tierce de Picardie. The final movement, (Allegro assai, ma tranquillo) contains a rising theme, articulated in turn, fugato-style, by the strings, joined by the piano in second lyrical theme for the full ensemble. The quintet ends with the strings in declamatory exuberance as the piano cascades down in a flourish.

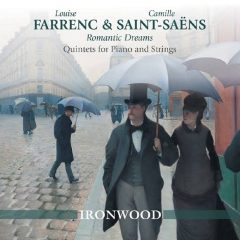

The booklet accompanying the CD is substantial, with a cover image by Caillebotte which evokes the mood of the music and the style of the era. Within its 20 pages, the detailed research and historical notes, list of references and biographies, complement this journey.

Romantic Dreams is exciting at many levels, from scholar to neophyte, for pure pleasure or for deeper study into the performance practices of the time.

Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©

.