CD Review: Pictures At An Exhibition/ Simon Tedeschi

On his new recording Pictures at an Exhibition for ABC Classics, pianist Simon Tedeschi combines two works from the Russian piano repertoire which share their status as masterworks, but which are at opposite ends of the spectrum of complexity.

First on the CD is Mussorgsky’s suite of 10 pieces, from which the recording takes its name, creating 16 tracks after the linking Promenades are added in. It’s a substantial suite containing many challenges for the pianist.

Following this is Tchaikovsky’s collection of 24 cameos, Album for the Young, opus 39, which is, in contrast, written especially for the younger pianist.

Pictures at an Exhibition was Mussorgsky’s homage to the memory of his friend, the Russian artist Viktor Hartmann, who had died in 1873 at age 39. A posthumous exhibition of Hartmann’s artwork inspired Mussorgsky to capture the paintings in music. The work was completed by the summer of 1874, yet it remained unknown until well after his death in 1881, when in 1886, his friend Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov edited and published the manuscript.The original version for piano was relegated in favour of the orchestral versions, the most popular of which was the transcription by Ravel (1922). Others including Sir Henry Wood (1918), Leopold Stokowski (1939), and Vladimir Ashkenazy (1982) also offered their interpretations of Mussorgsky’s music, not forgetting the 1971 version by the British pop group Emerson, Lake and Palmer.

Indeed, it is music that is richly textured and can be appreciated by its abstraction to the orchestral form. It was not until Russian pianist Svatislav Richter began to perform and recorded the piano version in the 1950s that the original enjoyed a renaissance (Horowitz’s 1947 piano transcription seems not have been as popular as Richter’s performances).

Tedeschi’s storytelling is compelling, affirming the mastery of Mussorgsky’s writing for the piano sans orchestral elaboration. The opening Promenade is authoritative and well paced, as are the subsequent Promenades; Tedeschi creates a simply grotesque Gnomus delivering rapid rippling figures which portray the scurrying gnome with a tinge of pathos. Tedeschi shrouds The Old Castle in veils of faded glory turning the passing troubadour’s performance into a lilting though plaintive melody. Ponderous chords bring the lumbering Oxen to life as the beasts of burden grapple with their load. As they pass, a very finely balanced and graded decrescendo carries them off into the distance.

With a lightness of touch, brilliant technical control and more than a hint of bravura, Tedeschi injects a spritz of lightness and whimsy into the more virtuosic movements, notably the Ballet of the Chicks in Their Shells, The Market Place and The Hut on Hen’s Legs. He pulls the pace right back for the ghostly two-part Catacombs before plunging into unbridled majesty in The Great Gate of Kiev.

Tedeschi adds a personal touch with his insights published in the CD insert, drawing on his family connections to place his performance in the context of his own journey of discovering art and architecture.

Tchaikovsky wrote Album for the Young, opus 39 for his seven-year-old nephew Vladimir ‘Bob’ Davidov. It’s technical elements and the images conveyed by the titles appeal directly to younger players.

As an adult playing children’s music, Tedeschi brings a well-balanced approach. His account is simple without being simplistic and mature without being melodramatic. He delivers a well-considered rendition that is nuanced and shaded with subtleties of tempo, tone, phrasing and articulation bringing into relief the beauty of the music.

The dance movements ebb and sway, The Doll’s Funeral is achingly sad and the four folk songs are sheer delight.

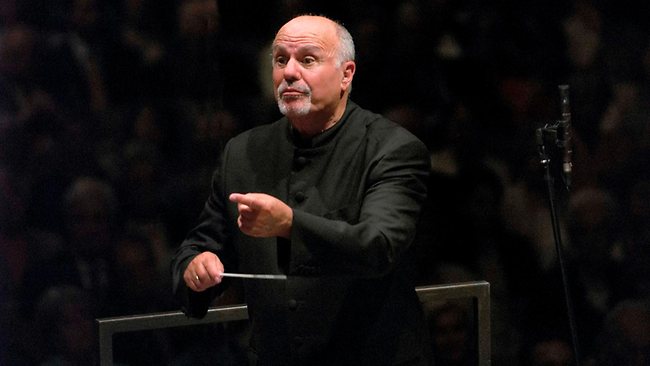

We’re not told on what piano this recording has been made. Whatever the instrument, it conveys a very bright sound – particularly in the upper register with more rounded lower tones. The booklet accompanying the CD has comprehensive historical and biographical information. The recording was made in February 2015 in the Eugene Goossens Hall of the ABC Centre in Ultimo Sydney under noted recording engineer Virginia Read.

This vivid visual elements of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and the appeal of Tchaikovsky’s Album for the Young make this recording apt for children. Adults will find their own level at which to appreciate it. Simon Tedeschi’s Pictures at an Exhibition is one for all ages.

Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©