Concert Review: Elgar’s Cello Concerto/ Sydney Symphony Orchestra

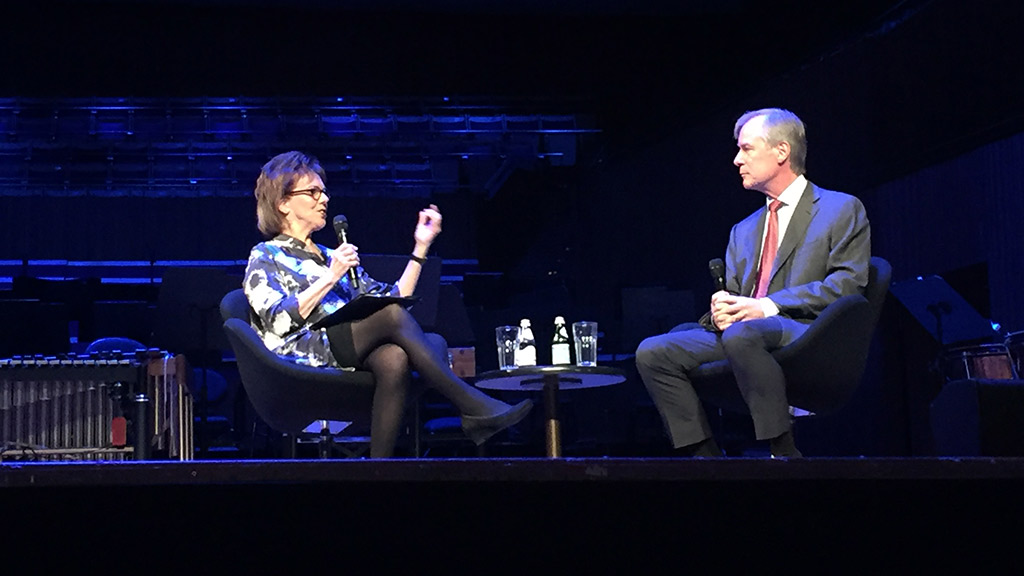

Elgar’s Cello Concerto/ Sydney Symphony Orchestra/ Runnicles/ Altstaedt

Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House

19 April, 2023

If ever sheer terror were to be depicted in music, then look no further than the Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93 by Dmitri Shostakovich, an Everest of a piece, performed brilliantly by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Principal Guest Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles, in the Concert Hall of the Sydney Opera House.

Also on the program were Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor, Op.85 with German-French cellist Nicolas Altstaedt and the introductory Mirage, by emerging composer Alex Turley (b 1995) commissioned by the SSO as part of its 50 Fanfares project an initiative launched in 2020 to nurture new composers.

Turley’s 5-minute innovative Mirage (2021) is scored for 4 Horns, 2 trumpets and trombones, bass trombone and tuba. Exploring the darker shades and the temporal and textural possibilities of the brass instruments, Turley positioned his musicians around the the concert hall with the main ensemble in the organ gallery. Performed in the presence of the composer, the echoing antiphonal sounds, shimmering scales and imitative lines, punctuated by chords, fluttering and sumptuous harmonies, made for an engaging piece which was warmly received by the audience. Whether new music lives or dies depends on the opportunity for repeat performances and a place in the concert repertoire. The recognition of this piece by its inclusion into the 50 Fanfares anthology is an affirmation the promise of both composer and composition.

Elgar’s cello concerto was his swan song, composed in 1919. Written as he was entering his 60s it is the voice of a man looking back on his life in all its many moods – mellow, raging, meandering, joyful and ultimately, accepting. Altstaedt is nowhere near his 60s, but along with conductor Sir Runnicles, had to decide between a heart-on-sleeve expression of Elgar’s masterwork or trimming back the indulgent, (some would say ‘bloated’) textures and letting the beauty of the notes speak for themselves. With instructions such as nobilmente, espressivo, teneramente, quasi-recitative and ad libitum sprinkled through the score, this is an intensely personal conversation, less rich in thematic development and relying more on its lush melodies, the performers’ interpretative powers and the many devices of string playing, to convey its message.

Runnicles and Altstaedt delivered an objective and restrained but deeply felt interpretation. Disciplined rubato and portamenti kept the momentum alive throughout the concerto. The opening bars were conversational without being overwrought, seeking tonality in Altstaedt’s delicate phrasing, light and fresh with minimal vibrato. The full orchestra finally revealed Elgar’s expansive, rolling theme, making its unmistakeable appearance in the home key. A boldly paced second movement maintained the intensity with Altstaedt performing a fiendish and meticulous spiccato, reminiscent of a man in a hurry with limited time left to get things done. The third movement was expansive with Altstaedt seizing the opportunity for more lyrical expression, the broad two-note phrases held over barlines, tugging at the tempi. The fourth movement with its touches of military grandeur was played in the style of macabre dance in which the narrator finally makes a deal with the dark side. Altstaedt had a final roar as he reprised the sobbing, quadruple stops of the opening before hurtling to the end of this quite splendid rendition. Altstaedt reappeared for a very welcome encore in a complete contrast of style, inviting Principal Cello Catherine Hewgill to join him in a magnificently ornamented slow movement from a sonata for two cellos by Jean-Baptiste Barrière, a composer of the French baroque,

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10, also in E minor, is a collision of art, politics, history and personal expression. It premiered in December 1953, some 9 months after the death of Stalin. With it, Shostakovich gives cathartic vent to the depths of despair and abject fear he surely experienced during Stalin’s regime. It is an arm-wrestle with the dictator; a duel to the death; who will blink first? In the end Shostakovich is the last man standing and he laughs for joy as the symphony comes to its raucous conclusion.

Musically, the symphony is a complex piece which exploits the possibilities of the woodwind and the brass instruments. The numerous solo moments from clarinet to piccolo, flute, horn, bassoon, cor anglais and oboe were impressively performed by the musicians of the orchestra. Sir Runnicles patiently built his well-paced arc in the first and longest movement. Like Elgar’s cello concerto, the lower strings began in rumbling darkness, until the mesmerising clarinet theme shone through. The flutes danced, tender and whimsical, the accents displaced; themes were stated and re-stated as the movement reached its shattering climax with piccolos shrieking their warning, crashing percussion, braying brass and jagged lines from the strings. The fear barely subsided with the two piccolos sounding their siren in the night above barely-there timpani, heightening the sense of dread.

The second movement, said to personify Stalin is unabated horror. With stabs from the strings, angular brass and woodwind lines and the thrum of the snare drum, Sir Runnicles and the orchestra furiously and at breathtaking pace, drew a macabre scene. This was the terror of the regime; the cold sweat of imminent arrest; this is Shostakovich fearing for his life.

As the symphony moved into the deeply personal sentiments of the two final movements, the orchestra introduced the theme of the third movement in canon and again we were treated to the pleasure of solos from some of the outstanding members of the wood wind and brass sections, notably Andrew Bain introducing the lucent ‘Elmira’ theme. There are critical moments as both soloists and ensemble introduce and intertwine the motifs of Shostakovich himself (DSCH) and the ‘Elmira’ theme. There is beautiful playing from bassoon, oboe, flute, cor anglais and timpani. The solo violin does get a moment of glory in the third movement, in a duet delicately played by Concertmaster Andrew Haveron and Bain.

Runnicles began the fourth movement Andante with the woodwinds playing in finely coloured quasi-Orientalist style, and he moved quickly to a maniacal Allegro. The shackles are off and it’s time to laugh hysterically at the past with swirling scales, delirious with joy and triumph. The DSCH motif was hammered insistently in affirmation. There were thunderbolts in the air. Stalin is dead. Shostakovich has prevailed.

Sir Runnicles honed a fine performance, from an expert ensemble which drew the colours and powerful dynamics of this monument of 20th century musical history. There are countless audio and visual recordings of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10, but little compares with the experience of hearing it ‘in the moment’ in all its beauty and complexity.

Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©