Concert Review: The Russian/ The Metropolitan Orchestra/ Benjamin Kopp

‘The Russian’

The Metropolitan Orchestra/ Benjamin Kopp, piano /Sarah-Grace Williams, conductor

16 April 2016

Eugene Goossens Hall, ABC Centre, Ultimo

The Metropolitan Orchestra, now in its seventh year, consists of notably young musicians whose performances display the energy and enthusiasm of youth. Their second MET concert for 2016 consisted of two major works by Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich conducted by their Chief Conductor, Sarah-Grace Williams. The Eugene Goossens Hall, in which it was held, has a fairly small seating capacity but it was nevertheless very gratifying to see the ‘house full’ sign posted on entering the foyer. The hall was designed principally for broadcasts and recordings and its rather dry acoustic emphasises clarity of sound at the expense of blend and warmth. This was reflected in the character of the sound produced by the orchestra and the solo pianist.

The first half of the concert consisted of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto with soloist Benjamin Kopp. Currently based in Berlin, Kopp maintains a solo performing career in Europe while also being the pianist in the Streeton Trio. He demonstrated a firm technique that was equal to the many difficult virtuoso passages in the work. In the first movement his playing emphasised the rhetoric of the music and displayed great strength and accuracy. In louder passages there was a tendency for the piano tone to harden somewhat – though this may have been partly due to the hall’s acoustic. In the languid second movement, Kopp’s interpretation was much more poetic with some very attractive phrasing and quieter playing. In the last movement, Kopp set off at a great pace, which seemed to be marginally faster than the orchestra was expecting. His technique was fully equal to the onslaught as he successfully rode over the difficult bravura passages including the notorious double octave challenge towards the end of the movement.

Sarah-Grace Williams’ conducting during the concerto was confident but she seemed to be playing things safe. The orchestra responded competently, with well-coordinated playing but with a less integrated blend than might have been obtained in a hall with a warmer acoustic. The violin sound, for example, might have a greater depth of tone in a different acoustic.

After the interval the orchestra launched into Shostakovich’s tenth symphony, first performed just nine months after the death of Stalin in 1953. It is an intensely powerful and often brutal commentary on Soviet society at the time. It is also a virtuoso work for any orchestra, presenting many opportunities for individual members to shine.

This performance was much more vivid than the Tchaikovsky concerto, with Williams able to stamp more of her own personality on the interpretation. Her conducting style is clear, energetically expressive, and it brings out the best from her players.

The mood of the first movement is one of profound unhappiness, of turmoil and despair. The opening was breathlessly tense, heightened by the impressive unanimity of the unison cellos and double basses. The mood was heightened by some expressive phrasing from clarinettist Andrew Doyle and some well blended ensemble playing from the lower brass instruments.

The short second movement is said to be a musical portrait of Stalin. It is a fierce march punctuated by strident shrieks of outrage graphically realised by the flutes and piccolos. The unremitting power and energy of the movement seemed to be relished by these young performers who played with enormous vigour, especially the militaristic brass and violent percussion.

The third movement is a macabre waltz during which Shostakovich introduces a motif based on his own name (DSCH). This was well played by the wind instruments, including some characterful solos by bassoonist Sarajane Hansen. Juxtaposed against this is a second motif which is derived from the name of a young student to whom Shostakovich was romantically attracted. This motif is eventually played a dozen times by the principal horn, Michael Wray, who negotiated these exposed passages without mishap and displayed a pleasantly full tone. The concertmaster, Dominique Guerbois, also successfully characterised several plaintive solo violin interjections.

The mood at the opening of the last movement is one of isolation and apparent futility, expressively conjured up by solos from the principal wind players including some distinguished oboe playing by Rie Tamaru. Towards the end of the symphony Shostakovich reintroduces the DSCH theme in a conclusion which is generally interpreted as a triumph of the artistic individual over the repression of the regime. Alternatively, the overblown coda may be construed as a sardonic commentary on the ironic necessity of projecting a triumphant exterior while in the depths of immense internal despair. Such is the fascinating ambiguity of Shostakovich’s symphonies. In any case, the conclusion of this performance pulled out all stops and ended in an intense blaze of fervent excitement with the orchestra sounding at their exhilarating best.

Many Sydney concertgoers will be unfamiliar with this orchestra and its background. The concert programme, the orchestra’s subscription brochure and its website could do more to provide more information about this fine orchestra and its members.

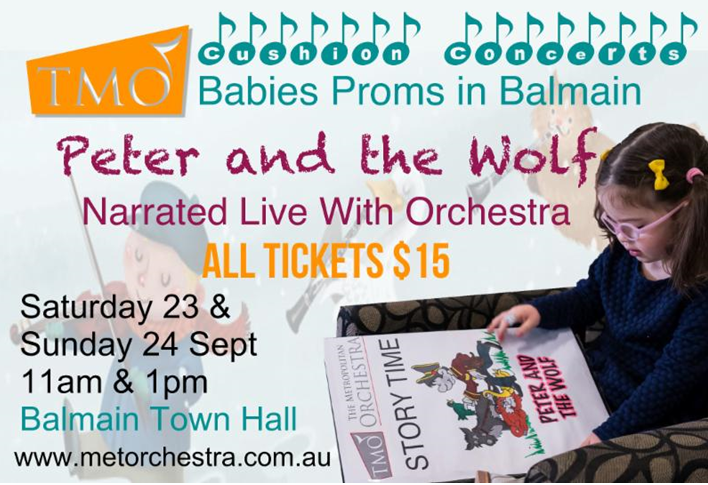

The orchestra’s next concert will be in the Eugene Goossens Hall on 11 June. It features Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony and Richard Strauss’s Horn Concerto No. 1 played by the orchestra’s principal horn, Michael Wray.

Larry Turner for SoundsLikeSydney©

Larry Turner is an avid attender of concerts and operas and has been reviewing performances for Sounds Like Sydney for several years. As a chorister for many years in both Sydney and London, he particularly enjoys music from both the great a capella period and the baroque. He has written programme notes for Sydney Philharmonia, the Intervarsity Choral Festival and the Sydneian Bach Choir and is currently part of a team researching the history of Sydney Philharmonia for its forthcoming centenary.