Madness, death and loss – this tenor never gets the girl

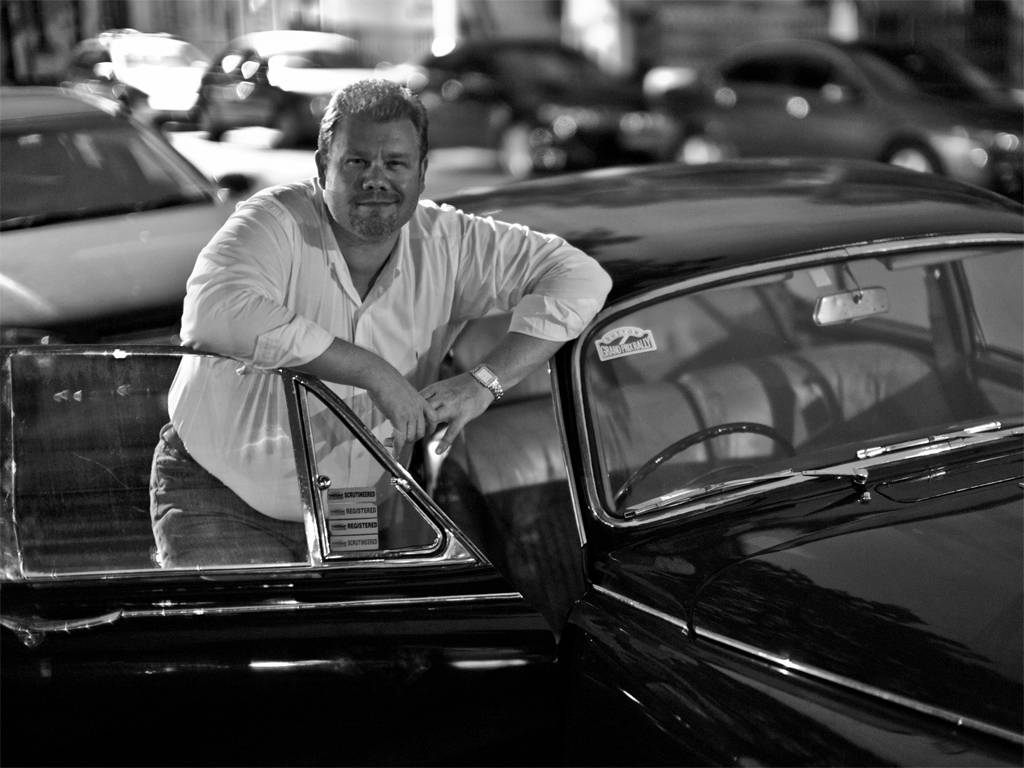

Tenor Stuart Skelton is soon to be performing again in Sydney. This is an interview he have to SoundsLikeSydney last year, on singing Wagner and on some of the characers he has portrayed in opera.

If you’re one who believes that in the end, the tenor gets the girl, even a cursory look at the roles sung by Heldentenor Stuart Skelton will soon dispel this misapprehension – Don Jose in Bizet’s Carmen, Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca, Hermann (Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame), Siegmund in Wagner’s Die Walküre, title roles in Rienzi and Lohengrin and Britten’s Peter Grimes. Not only do these characters lose the girl, they also kill, die or descend into madness. So, what is it about these roles that they sit so well with the Australian opera singer?

Stuart Skelton’s response was straightforward with a humour that belies the darkness of these characters : “I don’t know! I very rarely play funny or upbeat characters – I play Pagliacci too.” Becoming more serious, he added ” I guess I must respond to the music that makes its presentation on stage compelling. I don’t quite know how or why that happens, but I do find myself drawn as well, to the stories that inspired the music. Once you find the things that engage you and compel you as a performer, you’re probably going to get better and better at them, than the things that don’t engage you.”

I spoke with Stuart Skelton last week, whilst he was in Sydney spending time with his family, in between concerts in Hobart and Adelaide. In Hobart, he performed with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra conducted by Howard Shelley in Beethoven’s oratorio Christus am Oelberg. In Adelaide, he was to sing Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with Arvo Volmer and the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra.

Sydney audiences can hear Stuart Skelton when he returns in early December for his role debut as Hermann in the Sydney Symphony’s staged performance of Tchaikovsky’s opera Pique Dame, conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy. In 2013, he appears as Siegmund in Opera Australia’s nearly fully subscribed season of The Ring Cycle in Melbourne. The NSW born tenor started his singing career as a chorister at Sydney’s St Andrew’s Cathedral School. Winning the Australian Singing Competition Marianne Mathy Scholarship in 1991 took him to post-graduate studies overseas and the rest, as they say is history.

Away from Sydney, a day at the office for Stuart Skelton takes place at any of the opera houses of New York’s Met, Seattle, San Francisco, Paris, the English National Opera, the Vienna, Bavarian, Hamburg and Berlin State Operas, the Deutsche Oper Berlin and the Dresden Semperoper. His performances have been conducted by Vladimir Ashkenazy, Daniel Barenboim, Jiři Bèlohlavek, Christoph von Dohnanyi, Sir Mark Elder, Michael Tilson-Thomas, Christoph Eschenbach, Daniele Gatti, Mariss Jansons, James Levine, Lorin Maazel, Sir Simon Rattle, David Robertson, Donald Runnicles, and Franz Welser-Möst.

He has garnered high praise the world over for his performances from oratorio and art song, to opera, singing a generous repertoire from the romance of Wagner, Puccini and Mendelssohn, to the more modern works of Britten, Floyd, Berg and Stravinsky. His exceptional talent, versatility and the integrity of his musical and dramatic delivery define a career whose zenith is not yet in view.

The role of Hermann is reputedly a notoriously difficult one. Stuart Skelton agrees. ” It certainly looks like its going to present its challenges. One reason is that the character Hermann starts his journey already quite a little bit hazy. Most characters in opera develop along their journey. Hermann starts already obsessed and it bears itself out in the demands of the vocal writing. However, I enjoy the challenges – even those that stretch me and I think it’s a good thing for singers to extend themselves. More often than not I’ve been lucky that in doing this, I have found a new place and I have enjoyed the challenge, although at the time it seemed daunting.”

We settled into talking about the several Wagnerian roles that he’s sung, ranging from the early operas like Rienzi (Wagner’s third opera, written between 1838 and 1840, when Wagner was in his mid thirties) to Siegmund, in Die Walküre, written nearly 30 years later. How had Wagner’s writing for the voice changed over that time?

“The writing goes through a change even between Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman” (which premiered in 1843 and in which Stuart Skelton sings the role of Erik). “Rienzi is the the last of his genuinely Italian or French grand opera. In the ‘Dutchman‘ he’s really looking for a much more Germanic and through-composed voice than in Rienzi and 30 years later with The Ring Cycle, it all changes again. The philosophy that he’d been reading changes, along with what he rejected and what he embraced. The writing develops again between The Ring Cycle and Parsifal. Whilst composing the music for The Ring there was a big hiatus between Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, when Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg also appeared. So he goes through a number of different stages. My particular vocal challenge is, that as his writing moves from Rienzi through The Flying Dutchman on to the roles of Lohengrin, Sigmund and ultimately Parsifal, the writing becomes baritonal. The tessitura is not as demanding, though surely but slowly the orchestra becomes a lot bigger and takes a more prominent part of the process so that in the later composed parts of The Ring Cycle, the voice become more of a single part in the texture than a genuine solo instrument in the way that it would have been in the early operas.”

Was this change in tessitura through time, part of the a natural progression in the voice? “It’s probably only part of the process. The other part of that process is that Wagner’s concept of what it was to be a heroic changed over time from being the Nietzschean version with Siegried and Siegmund to a much more Schopenhauer based bleak outlook on the world. Wagner made it clear that whatever he wrote after Parsifal was going to be solely symphonic music – and you can hear this in the development of his compositional style. Certainly the heroes standout less and become more a part of the fabric not only of the music but of the story and the philosophy behind it.”

Several of the roles for which Stuart Skelton is best known are a testament to his versatility. Peter Grimes and Quint, Siegmund and Don Jose, for example, are at different loci in the stylistic spectrum. Despite the differences, he believes there are similarities. “Both Britten and Wagner, for instance, are extremely theatrical composers. They both wrote for the stage exceptionally well. However, one of the important differences is that whilst Wagner and the other composers were not writing for a specific voice or singer, Britten was writing all his tenor roles for Pears. That gives anyone who takes those roles, the same set of challenges. There is a set of vocal challenges that a tenor needs to negotiate, which represent what Pears was particularly good at. Wagner gives you a broader range of people to access and to emulate in terms of what works and what doesn’t, because he didn’t write for a particular voice. There is another important difference in that Wagner dealt with mythical content. Britten’s subject matter was much more personal, involving issues closer to his heart and that of the heart of the audience.”

Moving from roles to technique, and Stuart Skelton admits that there is nothing special that he does to maintain his rare Heldentenor range and timbre. “Given that I sing pretty much constantly and there are only about 8 weeks of the year when I’m not actually singing, I tend not to do anything that’s different from what I’m doing at the time in performance or rehearsals. I certainly don’t do anything that is repertoire specific. Before a rehearsal or a performance, I vocalise to warm up the voice as any singer would – just like an athlete would warm up their muscles before they compete. Singers are no different. I have a little routine that doesn’t really change. It seems to keep me in fairly good shape and puts me in good stead for performances.”

This August, Stuart Skelton will sing one of the roles that he has claimed as his own in a concert version of Peter Grimes, for the English National Opera conducted by Edward Gardner at the Proms in London. With a concert version of Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame in Sydney scheduled for December, I asked him how differently he needs to perform to convey the drama and the story sans the enhancements of theatre.

“Its a fine balance because there is level at which you can’t do too much, confined by orchestra behind you and not in costume. You also don’t get to interact with a set and props or with colleagues. That’s liberating in some ways because you get to concentrate on the sheer vocalism of the role which is no bad thing. It also allows the audience to really focus on the musical details without the distraction of a particular production. Ultimately, you find a way to infuse every performance with as much as you can bring to that performance, to work within the constraints to make the performance as compelling as possible, theatrically and vocally.”

In October, he reprises the role of Grimes for the New National Theatre Tokyo production conducted by Richard Armstrong, with Susan Gritton as Ellen and Jonathan Summers as Balstrode. This is the very first time that a British opera will be performed at the NNTT. Of course, it will be sung in English but with Japanese surtitles. Stuart Skelton is confident that it will be very well received. ” The music is incredibly beautiful and it is a very strong production so as a piece of theatre, it will be very powerful.” Artistic Director Otaka Tadaaki observes “It is also one that the Japanese people can easily relate to. The opera is set in a fishing village, and depicts the protagonists living in an insular community and the cruelty of their fates.” http://www.nntt.jac.go.jp/english/opera/e20000608_opera.html

Coincidentally, two of Stuart Skelton’s seemingly disparate roles – Hermann in Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame and Don Jose in Bizet’s Carmen have something in common. Carmen was reputedly Tchaikovsky’s favourite opera and their storylines revolve around soldiers and card games. “Indeed”, says Stuart Skelton, “they’re both composers who based their compositions on a whole string of really beautiful melodies and not so much on the Wagnerian phenomenon of everything happening at once. Tchaikovsky writes so beautifully for the voice, but he was probably a much more complicated individual than Bizet. I think that manifests itself as a certain melancholy in Tchaikovsky’s writing especially his vocal works. Bizet still had an enthusiasm, even if the music he was writing was not a not a particularly happy piece. I think Tchaikovsky’s melancholy is something that the Russians shared, from Rimsky-Korsakov to Rachmanninov and Tchaikovsky. It is unmistakable and Pique Dame has that in ‘spades’ “. The inextricable complexity of Stuart Skelton’s roles come to mind again – Britten’s operas too spoke of deep melancholy and marginalisation.

This begs the question whether he falls into these roles because they give expression to aspects of his persona that identify with exclusion and loss, or are these sentiments so far removed from his own experience that performing them is cathartic? “At a personal level, I don’t identify with those sentiments at all. It’s because of this that I can explore those characters comfortably and find a release or catharsis performing them. I can use these roles to express frustrations and the annoyances of life that are much more minor and compound them into something of a howling performance!” he chuckled.

And so to 2013 when thus far he is singing the role of Siegmund with at least four different companies, one of which is Opera Australia’s Melbourne Ring Cycle. We agree that keeping the approach fresh is critical to a good performance. “Working with different productions, conductors and colleagues helps keeps the material alive without any conscious effort from me. There is something new that comes to you – some new level that you can take it to.” Recently performing highlights of Die Walküre with Donald Runnicles, Stuart Skelton let me in on a conversation he’d shared with the conductor. “Donald was commenting on how he doesn’t get tired of this music, no matter how often he conducts it. There is a truism for me in that as well As a performer you find new ways to perform the same music and each production informs your interpretation and that can’t help but keep it fresh. Vocally there is a level as well, because you’re exploring ways of singing the role it as if it were written yesterday as opposed to a couple of hundred years ago.”

To soften the demands of constant touring, Stuart Skelton travels with his special friend, Pigmund, the Rock Pig (who really digs opera). Thankfully, Pigmund encountered no difficulties with quarantine on entering Australia. “He manages to charm his way through every time”. Rest assured, Pigmund has never placed the tenor at risk of swine’flu. Furthermore, there is absolutely no truth to the rumour that Pigmund is preparing for the male lead in Porky and Bess.

Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©