Nicola Benedetti avoids the crossover and stays current

You may not have noticed, but a famous violinist slipped in and out of Sydney this week. She has promised to return ‘soon’ so we can hear her at her craft.

Twenty five year old Nicola Benedetti was this year named ‘Female Artist of the Year’ at the Classical Brit Awards. Born in Scotland of Scottish Italian parents, she started playing the violin at 5. At 16, she was named 2004 BBC Young Musician of the Year and she has just released her 7th CD called The Silver Violin, heavily influenced by the classical music of the silver screen. It rocketed to No 1 on the UK classical chart, and No 32 on the UK Pop chart. It became the most successful album for a solo instrumentalist since Nigel Kennedy in 1991.

Benedetti made a fleeting visit through Sydney en route from New Zealand to Adelaide. In New Zealand, she performed with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. In Adelaide she will perform Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (on October 25th, 26th and 27th at the Adelaide Town Hall).

In Sydney, she conducted a workshop with the Sydney Youth Orchestra rehearsing the Korngold concerto, followed by a master-class and Q&A. The following day Benedetti visited Concord West Public School to donate a violin to their music department and to address the students.

An interest in pedagogy may seem unusual in one so young, but since 2005 Benedetti has been visiting schools throughout the UK in association with two charities – one (CLIC Sargent) that nurtures in children the enjoyment of playing classical music and the other (Sistema Scotland) that uses music making to build their confidence and personal skills.

The prospect of regular instrument practice may create in both parents and children alike, an abiding horror of learning to play a classical instrument. Benedetti agrees. “Unquestionably, making practice something that children will take the time to do is a challenge. But I think that there can be too much emphasis on promoting it as the most fun thing that they’re going to experience. That may be true for the first couple of weeks, until that slightly hysterical, enforced enthusiasm wears thin and the child realises very soon that it’s something about which you need to have a calm heartbeat, focus on, and realise that it’s something that you’re entering into for the long haul, that will grow day by day. It’s not instantaneous where you’ll see a result immediately. It’s something you need to stick to, enjoy, endure and understand the level of fulfilment that you will feel from a daily routine of honing a craft. To try to encourage that calm approach in a child is a reward that lasts longer and one that in the end, can be more effective.”

Benedetti speaks from experience. She continues ” I’ve tried the ‘Let’s have fun’ approach with a lot children I’ve taught; but I always find that this kind of initial over enthusiasm makes them feel more disappointed than anything else.” It’s about not creating unrealistic expectations and possibly even about creating a value system that will guide a child through life.

” You can get true enjoyment, happiness and a sense of pride and all the other emotions that are not mentioned as much as they should be when discussing the musical education of children. To have structure, to have a goal and to be focused is more of a priority. All of these words are much more valuable for the child that the word ‘fun’. When they’ve achieved something they feel great and they’re confident. That kind of feeling goes deeper and lasts longer. Learning to play an instrument individually, learning to play in an orchestra and the experience of a high art form like classical music – experiencing the combination of these three things is invaluable.”

The music on The Silver Violin takes inspiration from the seminal Violin Concerto by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Korngold (1897-1957) who won the 1938 Academy Award for his score to the film The Adventures of Robin Hood was an Austrian emigre who remained in Hollywood after the annexation of Australia by Germany during World War II. He was largely responsible for infusing film scores with the symphonic sound, and for bringing filmic grandeur to the concert hall. There are two other works by him on the CD, arias from his opera Die Tote Stadt, transcribed by him for violin as well as music by Shostakovich, Williams and Mahler, amongst others.

Asked what this anthology represents about her and her craft at this point in time, Benedetti affirms the central role of Korngold’s concerto on the recording. ” I hope the focus is on the Korngold violin concerto. It probably says the most about my craft alongside the Mahler piano quartet which is a demonstration of chamber music. I’ve taken Korngold, his life story, his work and his beliefs in music – in sharing amongst the genres and mediums of music. I’ve tried to display that music of his, obviously intended for classical performance – the violin concerto and the opera arias that he himself arranged for a violin – as well as a representation of everything that was inspired by him, in a sound word that he almost single handedly created. He inspired all film composers who followed him. His variety, his eclectic output and his success in combining these different elements of his compositions is something I feel, represented quite fairly on The Silver Violin.”

The influence went beyond Korngold to Mahler. ” It was very important to me to be able to include the Mahler piano quartet. Mahler was Korngold’s mentor and one of the first people to praise him for being the genius that he was. The music from Schindler’s List by John Williams is relevant in a slightly more abstract way. It was a Hollywood film dedicated to that period of time which dictated a lot of Korngold decisions depicting that point in time when it was Hollywood that saved Korngold’s life.”

I pointed out to Benedetti that Korngold’s opera Die Tote Stadt recently had a very popular run in Sydney. She was clearly excited. “You know, a lot of places are doing that opera for the first time – we’re going through an absolute revival of Korngold’s music. It’s underestimated how important it is for interpreters and performers to revive the music of a forgotten composer. So often in the past if there’s enough collective enthusiasm and excitement over that composer it can spread and lead to presenters, orchestral managers and people from concert halls across the world deciding to programme it. Audiences are exposed to it, they then fall in love with it and it becomes an ongoing circle of events that follows. I think we’re definitely in that place with Korngold.”

The conversation turned to the inevitable – the future of ‘classical’ music as the fine art to which Benedetti referred. We considered whether it has become too fine to survive without blurring the boundaries and disguising it under other labels, or without altering its substance.

Benedetti was emphatic in refuting the thought that classical music is doomed. “For as long as we exist as humans there will be a future for classical music. It’s too great and important an art form to ever die. There are millions more people aware of Beethoven’s music today that there were when he was alive – and there is no monetary reason for Beethoven to be as important as he is today. That just shows the power of the music. There is nothing that anyone stands to gain from keeping up his music and his message. The reason it is still so relevant is because of its power and its greatness.”

She continues, noting the broader role of the art form. “It’s one the greatest tools that we have to be able to understand our history and ourselves. For that reason I have no doubt at all that the greatest of classical music will always in peoples’ lives and will always be a part of human life.”

Benedetti’s following comments firmly placed her in the realm of ‘classical’ performance, despite a superficial similarity with ‘pop-over-cross-over’ hybrids. ” I do hope that in the 21st century, the direction that music takes will not be towards crossover music. I don’t believe that it’s in anyway an advancement of classical music. I don’t think that Vivaldi with a pop beat is any better – in fact, I think it’s much worse. Likewise, a pop song in Italian with an operatic voice doesn’t sound better to me – that too sounds worse. I don’t like the mixing. That may be my personal taste, but that’s my preference.” She offered valuable insights into the crossover genre. “The start of the crossover movement actually polarised a lot of people. The people involved in the crossover market became increasingly distant from the core of classical music and the classical music establishment became allergic to anything that was trying to be popular. It seems think that time is coming to an end. Crossover is not something that I would like to see as the conclusion of where classical music is today. Thankfully, I don’t believe that’s where we’re headed although it’s a popular thing to do and a lot of people like it.”

Benedetti’s confidence is founded in her belief in the values of ‘classical’ musicians. “There are so many substantial classical musicians who understand the importance of communicating with people; who understand the importance of creating ways for people to feel more connected with classical music and so the best musicians are willing to reach out, to communicate with their audience and bring the music to the people. For me, that is the ideal scenario – people who understand the core of the music, and who prioritise that and who won’t compromise regardless of whether it’s popular or not. They will stick to the core it but at the same time they’re willing to invest time and energy into ways of communicating that.”

The Silver Violin bears out her assertion that it is possible to be current without compromising values. “Ultimately” she says, “It communicates my very conscious effort to be thoughtful, creative and current with how I’m presenting CDs.”

Nicola Benedetti was interviewed by Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©

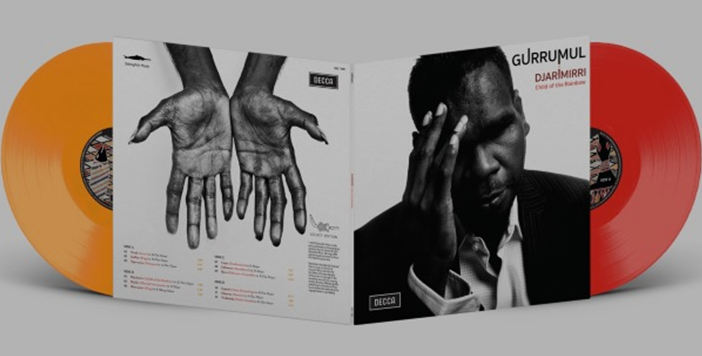

The Silver Violin is available on the Decca label Catalogue Number 478 3529.

Watch out for our review of The Silver Violin and check out the video of Nicola Benedetti in recording sessions.