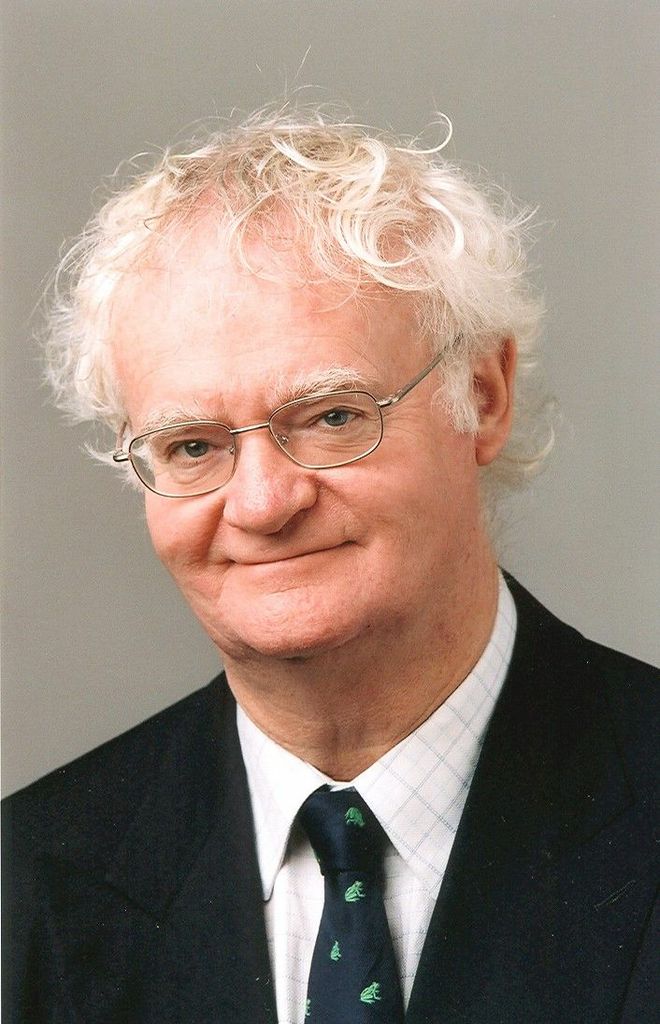

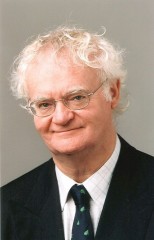

Into The Future With The Sydney Chamber Choir – Richard Gill Talks About His Vision As Incoming Director

Image supplied. Photo credit:: Jeff Busby.

This is a re-post of our April 2014 interview with the late Richard Gill AO. In memoriam.

“Being a conductor is kind of a hybrid profession because most fundamentally, it is being someone who is a coach, a trainer, an editor, a director” – Michael Tilson Thomas.

In the case of Richard Gill, OAM, the list goes on – there is hardly a major Australian ensemble which has not worked with him. A conductor of orchestras, choirs and opera, he is an educator and academic, a writer (his memoirs Give Me Excess of It was published by Pan MacMillian in 2012) and multi media star – he has appeared several times on ABC TV’s music quiz show Spicks and Specks, once dressed (badly) as Beethoven; he anchored the team of adjudicators and coaches in ABC TV’s Operatunity Oz in 2006, and has delivered a compelling talk for TEDxSydney on The Value of Music Education.

Until recently he was founding music director of Victorian Opera and is Artistic Director of the Sydney Symphony’s Education Programme. His seal on a project ensures that it will not just achieve excellence, but it will entertain, inform and educate as well.

Hardly surprising then that Richard Gill is to succeed Paul Stanhope as Musical Director of the Sydney Chamber Choir in 2016 when Stanhope steps aside to assume the role of Artistic Director of the Australia Ensemble. Richard Gill is no stranger to the Sydney Chamber Choir having been a patron of the choir since 2009. In fact he will conduct the ensemble in their performance of Faure’s Requiem on April 12th.

Speaking to SoundsLikeSydney, Gill drew on the Sydney Chamber Choir’s heritage as he talked of his vision for the choir’s future under his leadership.

“They have a very long track record (the choir was founded in 1975) and a wide range of repertoire and I intend to develop that” he declared. “We will refer to their past repertoire along with commissioning some new Australian music. Also, we plan to perform concerts in conjunction with other ensembles – instrumental ensembles or singers or combinations of these and mixing the repertoire quite significantly so that rather than focussing on one period of music in one concert, we might, in one concert cover several different periods and styles with significant works.”

True to his reputation as a passionate pedagogue, Gill plans to create a youth choir under the auspices of the Sydney Chamber Choir, introducing a substantial new facet to the choir’s activities. It seems like a daunting task to lure young adults away from any number of other pastimes that could be perceived as more entertaining or fashionable. Gill is unfazed. “There are lot of kids who love singing and who would happily come along to where singing is treated seriously. There are lots of choirs around where young people sing – the music is fine – but some want more – more challenge, more breadth and more depth in the repertoire. I also want to employ the resources of the Sydney Chamber Choir because the singers could work with the youth choir as vocal coaches and the members of the chamber choir have an extra responsibility in mentoring these young singers.

Reassuring words, for in Sydney, one might be forgiven for fearing that some aspects of choral music are in decline. Great swathes of the choral repertoire – both old and new – are rarely or never heard in performance. As a result, singers and conductors miss the opportunity to learn and perform this music, and audiences lose out on hearing live choral music in the context of a well constructed programme. ” While the Sydney Chamber Choir is around the repertoire that we can perform is still alive” says Gill firmly. ” We sing anything from 800 AD to Brahms, from Stravinsky to the present. We can also perform the passions, and all the Baroque classical repertoire easily. ”

What of the trend towards introducing visual elements into instrumental or vocal performances? Three recent Sydney productions have integrated dance into what were originally works written for voice. Have audiences become immune to more purist or meditative forms of entertainment, requiring the senses to be bombarded to hold their attention and explain a narrative that they should be considering for themselves?

Gill keeps an open mind. “I think it is one view of the way to do something. Often dancers don’t add anything to a performance and they often detract so I wouldn’t add dancers to a piece unless there was absolutely a very good reason for that piece to have dancers – but what I would consider doing is to construct a programme where the Sydney Chamber Choir is not necessarily singing for the entire programme.”

Tapping into audience tastes he continues “I think people do tire of an entire concert of unaccompanied choral singing – it is tough listening” he admits. “For example, if you do a whole programme of Monteverdi, after a while the soundscape doesn’t change – so while there would be some people who would adore a whole programme of Monteverdi others would like something different. So my view is to programme as much breadth and depth as possible with as much integrity as is possible without resorting to gimmicks – and I think that sometimes putting dancers in roles likes that is gimmicky” he says frankly.

Despite a respectable repository of ambition and talent and the availability of training in the nation’s most respected tertiary institutions there is a glaring lack of home-grown conductors in Australia. The major state orchestras and much of its opera are still led by musicians from abroad. “We don’t have a tradition of offering trainee conductors enough serious practical experience in conducting” he observes, adding “Europe offers a breadth of experience that just cannot be acquired here.”

“I had four trainees apprenticed to me for five years at a time and I saw them almost on a daily basis. I was able to give them opportunities that they would otherwise never have had – working in an opera company, working with orchestras and singers and with me. You can have post graduate courses in conducting but unless they’re actually in a professional position working with a mentor, it’s pretty meaningless and until the right training opportunities can be offered we’re going to be employing Europeans.” Those four trainees are all furthering their careers in Europe.

Does this reliance on European tradition extend to composition a well? Whilst Australia has a tradition of Western European music, it is geographically distant and culturally distinct. Australian composers have a low penetration of the global scene. I asked Gill if, in Australia we need to perform European music and why.

“My view” he elaborates “is that you’ve got to have the old with the new because the new reminds you of the old and the old was also new once- so the seeding in the repertoire is important and it is also important to develop choristers’ skills so that they’re challenged by the singing of new music and not just what is familiar. We don’t figure largely on the international music scene – and why would we – we’re a million miles away – but it doesn’t really matter whether we’re represented in Europe or not.”

The discussion extends to how music is structured. Should music composed in the 21st century adhere to familiar forms and structures? Music that has familiar patterns or a recurring theme is more easily recalled and recognised – does this lend itself to longevity in contrast with music that has no perceptible, memorable pattern when first heard?

Gill points out that an absence of ‘form’ (ie a specific pattern of themes and keys) is not unique to modern music and there is much early choral music that is led by ideas rather than structure.

It’s a fine line. “Patterns do make music more memorable but what you want from composers” he says “is an individual view of a piece. We don’t want all music to sounds exactly the same in the same pattern because that is what pop music does – it generates patterns that are familiar. and repetitive and have a very transient life.” He hastens to add that not all ‘pop’ music is like this – The Beatles being one exception. “There is an awful lot of ‘pop’ music that has a life of a few weeks and dies – and deservedly dies because it’s formulaic. So ‘form’ in that sense is often he kiss of death. What we want from a new piece is for it embody the composer’s view and it’s up to the composer to convince us that it’s worth listening to and what we remember from that.”

Here, his voice becomes more impassioned. “What matters here, more important than anything else is that music education is treated more seriously than it is – and that will have an impact on the way we think about music. If we get every child writing music, then we can start to build a culture which has informed views about music and has informed mechanisms with which to value, appreciate and understand music. That is what will change it” he concludes emphatically.

Shamistha de Soysa for SoundsLikeSydney©

Richard Gill conducts the Sydney Chamber Choir in Faure’s Requiem on April 12 at the City Recitall Hall